Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Saturday, December 06, 2008

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Rash and Rationality

Wednesday, May 07, 2008

Aspirational vs. Intellectual Viewing

The characters on The Hills are not real to me.

You have probably read that sentence as a criticism of the show, as meaning that the characters don't seem sufficiently life-like to capture my attention. And further, as an accusation of hypocrisy, since the show advertises itself as a reality show. But I don't mean either of those. I just mean that the characters on the show are constructed in pretty much the same way that characters are constructed in fictional shows. And they come into my living room the same way any sitcom character does. The knowledge that there are real people in Los Angeles whose lives are the raw material for the show enters my mind exactly as much as the knowledge that the steak on my dinner plate was once a cow. This may seem cold. It is. What's even colder is that, unlike that steak, I don't actually LIKE any of these characters.

This is probably largely a function of demographics: the show is most popular with tweenage girls, whereas I'm male and in my early 30's. The minimalist characterization that the show uses--long pauses on the nearly expressionless faces of the characters as they interact with each other--serves a different purpose for me than for more aspirational viewers. For young girls it offers an abundance of time to empathize with the character; the inscrutability is also a chance to practice reading the subtle verbal and facial clues that are key to complex social interaction. These are not things I'm interested in. For me these pauses are more awkward and noticeable--the fact that the conversations don't look natural mostly serves to defamiliarize classical continuity editing. So for most young girls the pleasure is in placing themselves in the melodramatic (and therefore meaningful) life of Lauren Conrad, while for me the pleasure is in feeling myself aware of (and therefore superior to) the constructed nature of the show.

I've been accused of intellectualism and elitism, and not for the last time. My writing is formal and exact. I know this turns some people off, even when I try to be accessible. But my point is that both of these ways of viewing the show involve complex cognitive processes. If you sat me and a tweenage girl in front of the The Hills and did brain scans on both of us, they would show equal amounts of mental activity. Her brain might show more empathic activity (brain scans can show that, right?) because of her identification with the characters, but that doesn't mean she's thinking about what she's seeing any less than I am. She's registering the social clues, and puzzling through the social strategy of the characters; I'm registering the framing choices and the cuts. But neither of us are more or less involved in the show. Whether she likes it more than me--well, I don't really see the point of that question.

You have probably read that sentence as a criticism of the show, as meaning that the characters don't seem sufficiently life-like to capture my attention. And further, as an accusation of hypocrisy, since the show advertises itself as a reality show. But I don't mean either of those. I just mean that the characters on the show are constructed in pretty much the same way that characters are constructed in fictional shows. And they come into my living room the same way any sitcom character does. The knowledge that there are real people in Los Angeles whose lives are the raw material for the show enters my mind exactly as much as the knowledge that the steak on my dinner plate was once a cow. This may seem cold. It is. What's even colder is that, unlike that steak, I don't actually LIKE any of these characters.

This is probably largely a function of demographics: the show is most popular with tweenage girls, whereas I'm male and in my early 30's. The minimalist characterization that the show uses--long pauses on the nearly expressionless faces of the characters as they interact with each other--serves a different purpose for me than for more aspirational viewers. For young girls it offers an abundance of time to empathize with the character; the inscrutability is also a chance to practice reading the subtle verbal and facial clues that are key to complex social interaction. These are not things I'm interested in. For me these pauses are more awkward and noticeable--the fact that the conversations don't look natural mostly serves to defamiliarize classical continuity editing. So for most young girls the pleasure is in placing themselves in the melodramatic (and therefore meaningful) life of Lauren Conrad, while for me the pleasure is in feeling myself aware of (and therefore superior to) the constructed nature of the show.

I've been accused of intellectualism and elitism, and not for the last time. My writing is formal and exact. I know this turns some people off, even when I try to be accessible. But my point is that both of these ways of viewing the show involve complex cognitive processes. If you sat me and a tweenage girl in front of the The Hills and did brain scans on both of us, they would show equal amounts of mental activity. Her brain might show more empathic activity (brain scans can show that, right?) because of her identification with the characters, but that doesn't mean she's thinking about what she's seeing any less than I am. She's registering the social clues, and puzzling through the social strategy of the characters; I'm registering the framing choices and the cuts. But neither of us are more or less involved in the show. Whether she likes it more than me--well, I don't really see the point of that question.

Hills Reading List

Mona Lisa Overdrive, William Gibson. Science Fiction, features a character who is the star of a reality show but feels herself increasingly trapped. How can she escape?

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers. For the MTV Real World audition chapter, and for the reality vs. fiction problem.

Watching Dallas, Ien Ang. Exactly what kind of pleasure do people get out of TV melodrama? What sociological conclusions can we draw from these shows. Nothing on reality TV here, but a good introduction to media studies.

Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia. An overblown and infuriating book, with absolutely no credibility, but it's fascinating in its depiction of the complex ways in which people use art and myth to create their personalities.

The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman. A game theoretical approach to the minutest types of everyday interactions. How we present ourselves, and how we examine other people's presentations of themselves for information.

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers. For the MTV Real World audition chapter, and for the reality vs. fiction problem.

Watching Dallas, Ien Ang. Exactly what kind of pleasure do people get out of TV melodrama? What sociological conclusions can we draw from these shows. Nothing on reality TV here, but a good introduction to media studies.

Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia. An overblown and infuriating book, with absolutely no credibility, but it's fascinating in its depiction of the complex ways in which people use art and myth to create their personalities.

The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman. A game theoretical approach to the minutest types of everyday interactions. How we present ourselves, and how we examine other people's presentations of themselves for information.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

Videos

Just so you don't get the impression that all I ever think about is The Hills, here's my other unhealthy obsession: Shiina Ringo. I've bugged some of you about her before, but here she is in convenient YouTube form, so you have no excuse now but to appreciate the genius. All things considered, this pretty much has to be one of my favorite music videos:

Cowboys? Samurai? And that's probably the best scream since "Frankie Teardrop" (that one's long). So it narrowly beats out the cosplay one, and the one with her playing electric guitar in a kimono.

Cowboys? Samurai? And that's probably the best scream since "Frankie Teardrop" (that one's long). So it narrowly beats out the cosplay one, and the one with her playing electric guitar in a kimono.

Would you get the impression that I really wanted to see it?

Lo: "I wonder if the neighbors have seen me naked yet."

Thursday, April 24, 2008

A Beautiful Lie

T-shirts with things written on them are not cool, but it's okay because Audrina is Rock 'n Roll. But she's not really Rock 'n Roll, because the shirt says she's beautiful. But actually she is Rock 'n Roll, because it also says that's a lie. But really she's not Rock 'n Roll, because she actually is beautiful.

Monday, April 21, 2008

No such thing as a guilty pleasure

No matter how disappointed many Hills fans might be at that New Yorker article (a pointless, lazy exercise in condescension that didn't even make a good faith effort to understand the show), it's not nearly as bad as this embarrassingly gushing review like this one of Gossip Girl. The conclusion to that article is that GG offers "profound social commentary." By which they mean: "The show mocks our superficial fantasies while satisfying them, allowing us to partake in the over-the-top pleasures of the irresponsible superrich without anxiety or guilt or moralizing." Um... let's just say that my definition of "profound" is very different from the one used by Ms. Pressler and Mr. Rovzar. "Social commentary," too. Or is that irony I smell? I can't quite tell, which in itself is a bad sign.

Actually I'm not sure Hills fans care that much about the New Yorker thing. The official MTV blog puts a positive spin on it, claiming that any mention in the New Yorker is an accomplishment, given the prestige of the magazine. They don't really need to take it seriously because the group of people who 1) read the New Yorker and 2) might possibly watch more than one episode of the show is approximately... me.

The two shows are actually pretty similar. Both are about the romantic lives of the hyperrich, centered on a Betty/Veronica rivalry; both include lots of references to text messaging and general new media connectivity as a nod to their interconnected audience. The difference between New York and LA is not that great. The real difference between the shows is that Gossip Girl allows for distanced, ironic viewing while The Hills does not. Kristen Bell's kitsch narration has a lot to do with this--because she doesn't appear in the show, the effect is to distance the viewer from the action and allow viewers to not feel guilty about indulging in their "superficial fantasies." Lauren Conrad's narration is limited to the "previouslies," and takes itself very seriously.

So we have people feeling superior to Gossip Girl but liking it anyway, and people feeling superior to The Hills and mocking it incessantly. None of this is surprising. But there's a way to feel superior to the show without mocking it or calling it a guilty pleasure--analyze it! Compare it to Antonioni, analyze narrative distance, name-drop Derrida and Barthes to show you've got more cultural capital than Heidi Montag. There's an obscurantist tendency in cultural studies to analyze the most disrespected aspects of popular culture; this may in the end be as condescending as simply dismissing them. To be honest, my appreciation of the show has very little to do with my feelings for its stars--Nancy Franklin is not far off when she says "I have yet to hear any character on the show say something interesting or funny." But the pleasures, for me anyway, lie elsewhere: I'm enough of a theory geek to actually enjoy all that cultural studies stuff.

Sunday, April 20, 2008

Friday, April 18, 2008

The Forces of Good and Evil at War for Heidi Montag's Soul

Reality TV, Reality Effects, and Realism

Justin at Songs About Buildings and Food hates this New Yorker article because it hates The Hills. I agree that the tone is a bit nasty, but the analysis is not too far off:

So here's an example of a tendency on The Hills that I mentioned last week, when a character enters a scene with their face obscured even though the entrance is staged. This is Audrina closing the door behind her as she comes home:

There's no logistical reason why the camera can't be moved a few feet in order to catch her face. This is a location that appears in every episode, and I guarantee that the producers know how to shoot here. So the question is, why obscure her face? What purpose does this serve?

I suggested last week that it has something to do with the "reality effect," a concept developed by literary theorist Roland Barthes. If there's a descriptive detail in a novel that serves no narrative or symbolic purpose, then its very meaninglessness is used to signify that the novel takes place in "reality." This is one way of pointing out that the "realism" of any artwork is not a result of how faithfully it reproduces the outside world, but how much it signals to the reader or viewer "this is real." But since TV and movies (leaving aside animation and special effects) are already constructed out of accurate pictures of the outside world, adding more details doesn't actually reinforce the realistic effect. The principle that "lack of meaning = reality" still holds, though, except that the lack of meaning comes not from extraneous details in content, but from unmotivated camera choices, in this case framing. So one reason this shot is included could be to signal to the audience that this is reality. "If this shot were planned, don't you think we would have planned it better? Therefore, it's obviously real."

But in the stylistic history of film, this has not been the usual way of signaling reality. Usually, you use long takes to better show a natural dialogue between characters, including things like awkward pauses and people talking over each other. You show scenes where very little happens in terms of plot. The Bicycle Thief is a classic example the realist school, or for something more recent try Four Months, Three Weeks, Two Days. This is precisely the opposite of what The Hills does, following Hollywood convention. Dialogue is chopped up into alternating shot/reverse-shot angles in order to 1) encourage spectators to identify with one of the characters and 2) streamline the conversation and make it flow. (1) And the weird thing is that The Hills is actually less streamlined than most Hollywood entertainment: after a conversation is broken down into its constituent parts, The Hills puts it back together with the awkward pauses either still there or possibly even deliberately edited in.

My point is that camera placement and editing in The Hills turn out to work against interpreting the show as "real"--instead, they highlight the show's constructedness. The show is purposely trying to look as much as possible like a Hollywood film, to the point of taking the Hollywood editing style to such extremes that the way it's constructed is blatantly obvious. And that includes the obscured faces, which are part of the currently popular "run-and-gun" style of filmmaking, where the best example is the Bourne films. This is also the reason the show is shot in widescreen.

1. By the way, this is basically the film-editing version of Taylorism, where actions taken by factory workers are broken down into the smallest possible pieces and then analyzed for efficiency--actually one word for this editing style is analytic. I'll say more about work on The Hills in a future post, to expand on my comments last time about industrial vs. information economies.

Dissertation progress yesterday: Finished Staging Fascism, which was excellent. Did about 40 pages of indexing/notetaking. Wrote about half a page, still on Nanook/primitivism.

Last movie watched: Crazed Fruit (1956), which is apparently the best of the Taiyozoku films. Based on an Ishihara Shintaro story, it was an influence on the French New Wave. Truffaut loved it. There's a lot to be said about the post-Occupation rejection/imitation of America by the Japanese counter-culture (if you can call it that).

“The Hills” isn’t aiming to stimulate or inspire; I think people watch it mostly to figure out why they’re watching it.Close, but I actually think people watch it mostly to figure out what they're watching, not why. Both questions are very difficult to answer, though, and either way this is more self-awareness than you get with most other shows.

So here's an example of a tendency on The Hills that I mentioned last week, when a character enters a scene with their face obscured even though the entrance is staged. This is Audrina closing the door behind her as she comes home:

There's no logistical reason why the camera can't be moved a few feet in order to catch her face. This is a location that appears in every episode, and I guarantee that the producers know how to shoot here. So the question is, why obscure her face? What purpose does this serve?

I suggested last week that it has something to do with the "reality effect," a concept developed by literary theorist Roland Barthes. If there's a descriptive detail in a novel that serves no narrative or symbolic purpose, then its very meaninglessness is used to signify that the novel takes place in "reality." This is one way of pointing out that the "realism" of any artwork is not a result of how faithfully it reproduces the outside world, but how much it signals to the reader or viewer "this is real." But since TV and movies (leaving aside animation and special effects) are already constructed out of accurate pictures of the outside world, adding more details doesn't actually reinforce the realistic effect. The principle that "lack of meaning = reality" still holds, though, except that the lack of meaning comes not from extraneous details in content, but from unmotivated camera choices, in this case framing. So one reason this shot is included could be to signal to the audience that this is reality. "If this shot were planned, don't you think we would have planned it better? Therefore, it's obviously real."

But in the stylistic history of film, this has not been the usual way of signaling reality. Usually, you use long takes to better show a natural dialogue between characters, including things like awkward pauses and people talking over each other. You show scenes where very little happens in terms of plot. The Bicycle Thief is a classic example the realist school, or for something more recent try Four Months, Three Weeks, Two Days. This is precisely the opposite of what The Hills does, following Hollywood convention. Dialogue is chopped up into alternating shot/reverse-shot angles in order to 1) encourage spectators to identify with one of the characters and 2) streamline the conversation and make it flow. (1) And the weird thing is that The Hills is actually less streamlined than most Hollywood entertainment: after a conversation is broken down into its constituent parts, The Hills puts it back together with the awkward pauses either still there or possibly even deliberately edited in.

My point is that camera placement and editing in The Hills turn out to work against interpreting the show as "real"--instead, they highlight the show's constructedness. The show is purposely trying to look as much as possible like a Hollywood film, to the point of taking the Hollywood editing style to such extremes that the way it's constructed is blatantly obvious. And that includes the obscured faces, which are part of the currently popular "run-and-gun" style of filmmaking, where the best example is the Bourne films. This is also the reason the show is shot in widescreen.

1. By the way, this is basically the film-editing version of Taylorism, where actions taken by factory workers are broken down into the smallest possible pieces and then analyzed for efficiency--actually one word for this editing style is analytic. I'll say more about work on The Hills in a future post, to expand on my comments last time about industrial vs. information economies.

Dissertation progress yesterday: Finished Staging Fascism, which was excellent. Did about 40 pages of indexing/notetaking. Wrote about half a page, still on Nanook/primitivism.

Last movie watched: Crazed Fruit (1956), which is apparently the best of the Taiyozoku films. Based on an Ishihara Shintaro story, it was an influence on the French New Wave. Truffaut loved it. There's a lot to be said about the post-Occupation rejection/imitation of America by the Japanese counter-culture (if you can call it that).

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Flipping the haters

Okay, it has come to my attention that certain people (you know who you are) are reading this and wondering how exactly The Hills might relate to my dissertation on French Fascist film reception. That's my fault for not being clear. This blog is basically a place for me to brainstorm about things I will write more formally in the dissertation, but sometimes I forget that and wander into intellectual masturbation, and the title of the blog becomes a little too apt.

The central assumption of the dissertation is that the ways in which a work of art is produced and distributed has political implications. So take film. A movie is (or used to be, anyway) a long strip of celluloid with pictures in sequence, which is projected onto a white screen in front of an audience that is sitting in the dark. Filmmakers address this audience in different ways. They can present them with performers who will do a song and dance to entertain them; they can show them footage of distant cultures or recreations of historical events in order to educate or persuade them; they can tell a story which will cause the audience to identify with the protagonist and involve itself or lose itself in the film. This last one is most interesting to me. Why would you want to lose yourself? What can someone make you do when you lose yourself? Is losing yourself in a film audience anything like losing yourself at a fascist rally?

This image is taken from Triumph of the Will (1935), the most famous Fascist film. Audiences can react in different ways to it. Many Germans would have watched it in order to be part of the mass ritual it depicts, to bind themselves to the nation as depicted in the film (the word fascism comes from an Italian word meaning "to bind"). Today we watch it to educate ourselves about a historical period and a political movement.

There were no French Fascist films, mostly because fascists never came to power in France (unless you count Vichy, which was too traditionally conservative to qualify). But there were a few very prominent French Fascist film critics--the critic for the most important literary daily, and the authors of the first history of film to be published in French, were all Fascist. Just like filmmakers, film critics make assumptions about the film audience. What do they want? Are they each individuals or do they form some kind of collective body? Are they bound to each other by language, by race, by class? The types of films critics like, and the things they say about them, tell us a lot about what they think about film audiences, which tells us a lot about their politics.

Okay, now take The Hills. The way in which this show is produced and distributed, the way in which people watch it, and the assumptions that critics make about it are all very different from the conditions surrounding 1930's films. Those differences also have a lot to do with what kind of audience watches the show, or what kind of audience is created by the show. Contrary to what most people assume, the show rewards and encourages a very sophisticated viewing, a type of viewing that is simultaneously absorbed in the plot and detached from it. Younger viewers are probably on average better at this than older viewers. Here's Lauren with her iPod. Notice that one earbud is out--she's multitasking, listening and not listening at once.

The reason that The Hills is better at this than other shows is that it destroys the difference between reality and fiction. All actors on the show are living their real lives, but those lives just happen to include an entourage of cameramen, make-up people, wardrobe, etc. The show has been criticized because it pre-plans scenes, makes suggestions to its actors about what might make for good TV, and even reshoots some scenes. Critics claim that this destroys its legitimacy as a reality show. But the show isn't aiming for this kind of legitimacy--it makes no claims to be educating its audience about reality. Actually very few reality shows do.

So you would assume that the show invites its audience to become absorbed in the story, to identify with one or more of the characters as they would in a fictional drama. You can indeed watch it like a fictional drama, which confuses some first-time viewers who aren't familiar with how the show works. "Is this a reality show? It can't be, because it's so well scripted and so well shot." But if you watch it only in this way, you're missing out on all the fun stuff, which comes from watching the double meaning of everything that occurs--every line and every action is motivated by the show's narrative, but even more so by the characters' attempts to position themselves in the public eye.

An example from last week's show: Heidi and Lauren have had a major fight, which was the big event of last season, and Heidi moved out of the apartment they shared and are no longer talking. Heidi is now trying to renew her friendship with Audrina, Lauren's roommate, and stops by the apartment ostensibly to pick up some stuff she left behind when she moved out. When Lauren gets home, she learns about this from Audrina (I'm paraphrasing):

Audrina: Heidi was here.

Lauren: What, she just stopped by?

Audrina: No, she called and said she wanted to pick up some stuff.

Lauren: Did she just pick up her stuff and leave?

Audrina: She sat down for a minute.

When Lauren asks whether Heidi just stopped by, we can interpret that as her asking whether this scene was filmed. Will the Heidi-Audrina encounter be part of the show? Yes, it will. Lauren must now proceed knowing that millions of people may eventually watch her asking Audrina what happened. She solicits more information from Audrina, and the extended drama of Heidi vs. Lauren continues. The point is that we have just glimpsed a small part of the way the show is made. Very few TV shows or movies are willing to expose their conditions of production, and most of those that do play it for laughs. The Hills not only exposes this, it does it in virtually every scene, and it turns it into the whole subject of the show. Viewers constantly shift back and forth between what they know of these people in real life and what they see of them on the show, between distraction and involvement.

What does this have to do with politics? Well, Heidi has recently endorsed John McCain for president, but that's not what I'm interested in. I'm concerned with what types of audiences are created by different types of movies or TV shows. I hope I've shown how the audience for the Hills is potentially very sophisticated. It is more able to evaluate official visual images in light of other sources of information. The show is an example of intertextuality, which means that it exists not only as a TV show but also as every single other medium in which these actors are mentioned. The photo of Lauren above, for example, is a "behind-the-scenes" photo that I got off the MTV website. But Lauren is in character for that photo, as she is her entire life, and so that photo is part of the show, in a very literal way. So is every magazine article, every late show spot that Lauren or Heidi or any of them appear on. This very blog post is actually part of the show. So are you, the reader.

The implications of this type of audience are still being worked out, which is what makes the show so cutting-edge. One thing to watch is how people respond to the fact that there are now people out there whose job it is to BE THEMSELVES. As we move from a product-based economy (where real things are manufactured) to a service-based economy (where nothing but information is produced), this is an important question. Will this shift allow all of us to get paid for being ourselves? Is this really what we want? Will it make us happy? Tune in next week to see.

Dissertation progress yesterday: Read half of Staging Fascism, about a crazy theater project in Fascist Italy which attempted to use a new type of theater (involving a truck as the main character, not even kidding) in order to create a new, fascist, audience. Indexed and took notes on about 20 pages of newspaper articles. Wrote about a paragraph on fascist opinion of early documentary film.

Movie I watched last night: Eternity and a Day (2001), by Theo Angelopoulos. Contemplative movie about a dying Greek poet, and his last day remembering his past and dealing with his present. Long takes, slow camera movement.

The central assumption of the dissertation is that the ways in which a work of art is produced and distributed has political implications. So take film. A movie is (or used to be, anyway) a long strip of celluloid with pictures in sequence, which is projected onto a white screen in front of an audience that is sitting in the dark. Filmmakers address this audience in different ways. They can present them with performers who will do a song and dance to entertain them; they can show them footage of distant cultures or recreations of historical events in order to educate or persuade them; they can tell a story which will cause the audience to identify with the protagonist and involve itself or lose itself in the film. This last one is most interesting to me. Why would you want to lose yourself? What can someone make you do when you lose yourself? Is losing yourself in a film audience anything like losing yourself at a fascist rally?

This image is taken from Triumph of the Will (1935), the most famous Fascist film. Audiences can react in different ways to it. Many Germans would have watched it in order to be part of the mass ritual it depicts, to bind themselves to the nation as depicted in the film (the word fascism comes from an Italian word meaning "to bind"). Today we watch it to educate ourselves about a historical period and a political movement.

There were no French Fascist films, mostly because fascists never came to power in France (unless you count Vichy, which was too traditionally conservative to qualify). But there were a few very prominent French Fascist film critics--the critic for the most important literary daily, and the authors of the first history of film to be published in French, were all Fascist. Just like filmmakers, film critics make assumptions about the film audience. What do they want? Are they each individuals or do they form some kind of collective body? Are they bound to each other by language, by race, by class? The types of films critics like, and the things they say about them, tell us a lot about what they think about film audiences, which tells us a lot about their politics.

Okay, now take The Hills. The way in which this show is produced and distributed, the way in which people watch it, and the assumptions that critics make about it are all very different from the conditions surrounding 1930's films. Those differences also have a lot to do with what kind of audience watches the show, or what kind of audience is created by the show. Contrary to what most people assume, the show rewards and encourages a very sophisticated viewing, a type of viewing that is simultaneously absorbed in the plot and detached from it. Younger viewers are probably on average better at this than older viewers. Here's Lauren with her iPod. Notice that one earbud is out--she's multitasking, listening and not listening at once.

The reason that The Hills is better at this than other shows is that it destroys the difference between reality and fiction. All actors on the show are living their real lives, but those lives just happen to include an entourage of cameramen, make-up people, wardrobe, etc. The show has been criticized because it pre-plans scenes, makes suggestions to its actors about what might make for good TV, and even reshoots some scenes. Critics claim that this destroys its legitimacy as a reality show. But the show isn't aiming for this kind of legitimacy--it makes no claims to be educating its audience about reality. Actually very few reality shows do.

So you would assume that the show invites its audience to become absorbed in the story, to identify with one or more of the characters as they would in a fictional drama. You can indeed watch it like a fictional drama, which confuses some first-time viewers who aren't familiar with how the show works. "Is this a reality show? It can't be, because it's so well scripted and so well shot." But if you watch it only in this way, you're missing out on all the fun stuff, which comes from watching the double meaning of everything that occurs--every line and every action is motivated by the show's narrative, but even more so by the characters' attempts to position themselves in the public eye.

An example from last week's show: Heidi and Lauren have had a major fight, which was the big event of last season, and Heidi moved out of the apartment they shared and are no longer talking. Heidi is now trying to renew her friendship with Audrina, Lauren's roommate, and stops by the apartment ostensibly to pick up some stuff she left behind when she moved out. When Lauren gets home, she learns about this from Audrina (I'm paraphrasing):

Audrina: Heidi was here.

Lauren: What, she just stopped by?

Audrina: No, she called and said she wanted to pick up some stuff.

Lauren: Did she just pick up her stuff and leave?

Audrina: She sat down for a minute.

When Lauren asks whether Heidi just stopped by, we can interpret that as her asking whether this scene was filmed. Will the Heidi-Audrina encounter be part of the show? Yes, it will. Lauren must now proceed knowing that millions of people may eventually watch her asking Audrina what happened. She solicits more information from Audrina, and the extended drama of Heidi vs. Lauren continues. The point is that we have just glimpsed a small part of the way the show is made. Very few TV shows or movies are willing to expose their conditions of production, and most of those that do play it for laughs. The Hills not only exposes this, it does it in virtually every scene, and it turns it into the whole subject of the show. Viewers constantly shift back and forth between what they know of these people in real life and what they see of them on the show, between distraction and involvement.

What does this have to do with politics? Well, Heidi has recently endorsed John McCain for president, but that's not what I'm interested in. I'm concerned with what types of audiences are created by different types of movies or TV shows. I hope I've shown how the audience for the Hills is potentially very sophisticated. It is more able to evaluate official visual images in light of other sources of information. The show is an example of intertextuality, which means that it exists not only as a TV show but also as every single other medium in which these actors are mentioned. The photo of Lauren above, for example, is a "behind-the-scenes" photo that I got off the MTV website. But Lauren is in character for that photo, as she is her entire life, and so that photo is part of the show, in a very literal way. So is every magazine article, every late show spot that Lauren or Heidi or any of them appear on. This very blog post is actually part of the show. So are you, the reader.

The implications of this type of audience are still being worked out, which is what makes the show so cutting-edge. One thing to watch is how people respond to the fact that there are now people out there whose job it is to BE THEMSELVES. As we move from a product-based economy (where real things are manufactured) to a service-based economy (where nothing but information is produced), this is an important question. Will this shift allow all of us to get paid for being ourselves? Is this really what we want? Will it make us happy? Tune in next week to see.

Dissertation progress yesterday: Read half of Staging Fascism, about a crazy theater project in Fascist Italy which attempted to use a new type of theater (involving a truck as the main character, not even kidding) in order to create a new, fascist, audience. Indexed and took notes on about 20 pages of newspaper articles. Wrote about a paragraph on fascist opinion of early documentary film.

Movie I watched last night: Eternity and a Day (2001), by Theo Angelopoulos. Contemplative movie about a dying Greek poet, and his last day remembering his past and dealing with his present. Long takes, slow camera movement.

Tuesday, April 08, 2008

Hills Blogging

So let me just say first that The Hills is the most complex show on TV. This is Cold War level game theory going on here--how much information do you give to your adversary/ally/frenemy? And how much do you trust the information they give you? Keep in mind that "information" here includes not just facts and opinions but also facial expressions and body language. In addition, the RAND guys never had to deal with the reality-TV component to this--everything that's filmed WILL eventually reach all interested parties, either through the producers or when the show finally airs. This season looks like it's going to be about détente--the slow and difficult process of accomplishing a reconciliation.

Game theory aside, the most interesting thing about the show is the uncertain relation between the storyline (presented within and across the episodes) and the actual lives of the characters (namely, anything that is not filmed by MTV), which is absolutely mind-bending. The narrative is never confined to what we see on the show--every single tabloid piece, every public appearance, every blog entry, is actually part of the show. Some people have mentioned how the show has the most expansive authorship ever, since the actors are all involved in creating the story, but it also proves Derrida right: there is no outside-the-text.

The first question I have--and it may seem trivial given all that lit theory, but I want to start to try to bring visual analysis into the discussion--is why do so many characters make entrances with their faces obscured? Entrances are obviously planned and staged, so why create that second of confusion when you see that a character has entered an apartment but don't see who it is? To create a reality effect?

The second question is also visual--is there a pattern to the "pillow shots" between scenes? Do they comment on the upcoming scene? What position does the narration take? They are not like Ozu's pillow shots, which always place the action. These shots signify "Los Angeles," before providing an exterior establishing shot--"Lauren and Audrina's apartment," or wherever. What's the point of the aerial shots?

Game theory aside, the most interesting thing about the show is the uncertain relation between the storyline (presented within and across the episodes) and the actual lives of the characters (namely, anything that is not filmed by MTV), which is absolutely mind-bending. The narrative is never confined to what we see on the show--every single tabloid piece, every public appearance, every blog entry, is actually part of the show. Some people have mentioned how the show has the most expansive authorship ever, since the actors are all involved in creating the story, but it also proves Derrida right: there is no outside-the-text.

The first question I have--and it may seem trivial given all that lit theory, but I want to start to try to bring visual analysis into the discussion--is why do so many characters make entrances with their faces obscured? Entrances are obviously planned and staged, so why create that second of confusion when you see that a character has entered an apartment but don't see who it is? To create a reality effect?

The second question is also visual--is there a pattern to the "pillow shots" between scenes? Do they comment on the upcoming scene? What position does the narration take? They are not like Ozu's pillow shots, which always place the action. These shots signify "Los Angeles," before providing an exterior establishing shot--"Lauren and Audrina's apartment," or wherever. What's the point of the aerial shots?

Wednesday, April 02, 2008

Flowing Cognition

Friday, March 14, 2008

If you see only one movie this year...

...then you will probably miss some of the complexities, since watching movies takes practice. You should probably stick with something easy to follow. If you watch a lot of movies, on the other hand, you will probably find it easy to enjoy some movies that others find strange or disturbing.

Note: this is not quite an endorsement of the Everything Bad is Good For You idea. Johnson argues that lots of "trashy" TV shows and video games are good learning tools because their complex narratives make high conceptual demands on their audiences. He has some good things to say about film too, arguing that the Lord of the Rings trilogy is narratively more demanding than the Star Wars trilogy--using the number of characters as a rough measure of narrative complexity. I'll grant him that, as a generalization. But he goes on to say that movies are not quite as good as TV or video games because the shorter time limit for movies limits narrative complexity. Here's where I think he's wrong.

First, complexity of narrative is not the same as amount of narrative. Which is harder to follow: a tightly plotted show like 24 which provides a clear McGuffin and where each character has only one motive at any time, or something like Pulp Fiction where 90% of the talking is entirely irrelevant to the plot but which contains a few narrative ellipses and disorderings? My point is that time constraint has nothing to do with how demanding a narrative is.

The second issue I have with his dismissal of film is that he focuses solely on narrative, explicitly dismissing "quicksilver editing" as something that might challenge an audience. While it's true that faster editing is not necessarily harder to follow--this is the whole point of the term "intensified continuity" as I understand it--it's not true that "narrative" is the only thing spectators must engage with cognitively. Or to be more precise, film narrative is built from things like framing and editing, and spectators have access to the plot only through these cinematic techniques. In movies that differ from usual Hollywood practice, the viewer will be cognitively engaged with "form" as much as or even more than "content." This is why slow movies can be harder to follow than fast movies.

Note: this is not quite an endorsement of the Everything Bad is Good For You idea. Johnson argues that lots of "trashy" TV shows and video games are good learning tools because their complex narratives make high conceptual demands on their audiences. He has some good things to say about film too, arguing that the Lord of the Rings trilogy is narratively more demanding than the Star Wars trilogy--using the number of characters as a rough measure of narrative complexity. I'll grant him that, as a generalization. But he goes on to say that movies are not quite as good as TV or video games because the shorter time limit for movies limits narrative complexity. Here's where I think he's wrong.

First, complexity of narrative is not the same as amount of narrative. Which is harder to follow: a tightly plotted show like 24 which provides a clear McGuffin and where each character has only one motive at any time, or something like Pulp Fiction where 90% of the talking is entirely irrelevant to the plot but which contains a few narrative ellipses and disorderings? My point is that time constraint has nothing to do with how demanding a narrative is.

The second issue I have with his dismissal of film is that he focuses solely on narrative, explicitly dismissing "quicksilver editing" as something that might challenge an audience. While it's true that faster editing is not necessarily harder to follow--this is the whole point of the term "intensified continuity" as I understand it--it's not true that "narrative" is the only thing spectators must engage with cognitively. Or to be more precise, film narrative is built from things like framing and editing, and spectators have access to the plot only through these cinematic techniques. In movies that differ from usual Hollywood practice, the viewer will be cognitively engaged with "form" as much as or even more than "content." This is why slow movies can be harder to follow than fast movies.

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Another Jennifer Jason Leigh Post

In my continuing quest to say new things about movies that are so old no one cares about them anymore (see the Last Days of Pompeii post below), I want to take on Fast Times at Ridgemont High, which I saw this weekend.

This is an entirely different experience from seeing it on TV, and not in the way you think.

Sure, you get to see Phoebe Cates topless, which is nice if you're into that kind of thing. But the other scenes that get cut, the ones where Jennifer Jason Leigh gets naked (yes, there are two of them), are so crucial to the plot that leaving them out changes the movie entirely. When I Love the 80's talking heads go on about how cool Spicoli was or admit how many times they jerked off to the bathing suit scene, they give the impression that this was some kind of raunchy proto-American Pie. Roger Ebert basically says the same thing with less approval, calling the movie sexist. (Is that an apology for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls? None needed, actually.) Here's his argument:

slut "promiscuous sex machine": she has sex twice in the period of a year.

(Spoilers here.) The disastrous second sex scene, in the poolhouse, actually entirely changes our interpretation of two different characters. The next scene has Leigh and Cates talking about how long their respective lovers take. Having seen Mike's little incident, we know that Leigh is lying when she says he took 15 minutes. So we interpret Cates's answer (30-40 minutes) as a lie too. In fact, I think we're supposed to assume that Cates's long-distance boyfriend is entirely imaginary, an excuse she uses to make herself seem sophisticated even though she's scared to death of sex. Mike also comes across as both less promiscuous and less honest. He flakes out on the abortion not because he's an insensitive jerk, but because he's embarrassed. All his talk about how great he is with women is just a bluff to hide his inadequacies. Okay, so he's still a jerk, but he and Cates's character are also more human than they appear on TV. And way more human than any character in American Pie.

This is an entirely different experience from seeing it on TV, and not in the way you think.

Sure, you get to see Phoebe Cates topless, which is nice if you're into that kind of thing. But the other scenes that get cut, the ones where Jennifer Jason Leigh gets naked (yes, there are two of them), are so crucial to the plot that leaving them out changes the movie entirely. When I Love the 80's talking heads go on about how cool Spicoli was or admit how many times they jerked off to the bathing suit scene, they give the impression that this was some kind of raunchy proto-American Pie. Roger Ebert basically says the same thing with less approval, calling the movie sexist. (Is that an apology for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls? None needed, actually.) Here's his argument:

[Leigh's] sexual experiences all turn out to have an unnecessary element of realism, so that we have to see her humiliated, disappointed, and embarrassed. Whatever happened to upbeat sex? Whatever happened to love and lust and romance, and scenes where good-looking kids had a little joy and excitement in life, instead of all this grungy downbeat humiliation? Why does someone as pretty as Leigh have to have her nudity exploited in shots where the only point is to show her ill-at-ease?Basically, Ebert has no problem with sex in movies as long as it's unrealistic. He seems in denial about the fact that the movie is almost feminist. The main point is that all of the boys are losers who are so lost in their male fantasies that they can't satisfy Leigh. She's not humiliated or embarrassed, she's actually pretty much in control of the situation. Yes, she's disappointed, but not as much as Ebert is at not getting to see more beautiful people fucking. At least Leigh's character is honest about her situation, whereas Ebert has to hide his disappointment behind false concern about Leigh being exploited. (Shorter Ebert: "Only ugly people should be exploited to show sexual embarrassment; beautiful people should be exploited to make me hard.") And by the way, he's wrong when he calls her a

(Spoilers here.) The disastrous second sex scene, in the poolhouse, actually entirely changes our interpretation of two different characters. The next scene has Leigh and Cates talking about how long their respective lovers take. Having seen Mike's little incident, we know that Leigh is lying when she says he took 15 minutes. So we interpret Cates's answer (30-40 minutes) as a lie too. In fact, I think we're supposed to assume that Cates's long-distance boyfriend is entirely imaginary, an excuse she uses to make herself seem sophisticated even though she's scared to death of sex. Mike also comes across as both less promiscuous and less honest. He flakes out on the abortion not because he's an insensitive jerk, but because he's embarrassed. All his talk about how great he is with women is just a bluff to hide his inadequacies. Okay, so he's still a jerk, but he and Cates's character are also more human than they appear on TV. And way more human than any character in American Pie.

Wednesday, March 05, 2008

Celine and Globalization

No, not that Céline.

That Celine.

I just finished reading Carl Wilson's book, which I highly recommend to anyone who's a music snob or wants to understand a music snob. I won't say much about the Bourdieu aspect of it, which I think makes a lot of sense. I'm more interested in his argument for music criticism that is more personal, "a tour of aesthetic experience, a travelogue, a memoir." He does this well for Celine, relating her to his divorce and his feelings about getting older, in ways that make sense of why he doesn't like Celine but why he feels conflicted about not liking her.

The most exciting pop music discoveries I've made in the past few years have all been foreign: MIA, Françoise Hardy, Fela Kuti, and Shiina Ringo. This is not to say that these are now my favorite artists, just that there's an extra element of surprise and pleasure in finding something slightly strange or exotic that still sounds great and totally accessible. All four make music rooted in their respective national traditions (although MIA is probably more globalized), but they all respond to dominant American musical genres. My personal aesthetic travelogue would include the fact that I'm not entirely happy with America or with living in America. So my attraction to this stuff is political and personal. MIA and Fela are both explicitly political, while Hardy and Shiina come from countries I've lived in.

One of Wilson's arguments is that because Celine is Quebecoise, people around the world hear her as just slightly non-American. He might have said more about why this is attractive to so many people right now, but the fact that she's huge in Iraq right now is a huge hint. People can hear the positive aspects of America, especially the rags-to-riches dream, without also hearing the music as culturally oppressive. My point is that my appreciation of foreign music (and movies too, probably) is the mirror image of their appreciation of Celine. Both tastes are structured around an understanding of America as the cultural superpower, both attractive and threatening.

Which is also to say that if I were Iraqi, then maybe I'd like her too. But I'm American, so I think she sucks.

That Celine.

I just finished reading Carl Wilson's book, which I highly recommend to anyone who's a music snob or wants to understand a music snob. I won't say much about the Bourdieu aspect of it, which I think makes a lot of sense. I'm more interested in his argument for music criticism that is more personal, "a tour of aesthetic experience, a travelogue, a memoir." He does this well for Celine, relating her to his divorce and his feelings about getting older, in ways that make sense of why he doesn't like Celine but why he feels conflicted about not liking her.

The most exciting pop music discoveries I've made in the past few years have all been foreign: MIA, Françoise Hardy, Fela Kuti, and Shiina Ringo. This is not to say that these are now my favorite artists, just that there's an extra element of surprise and pleasure in finding something slightly strange or exotic that still sounds great and totally accessible. All four make music rooted in their respective national traditions (although MIA is probably more globalized), but they all respond to dominant American musical genres. My personal aesthetic travelogue would include the fact that I'm not entirely happy with America or with living in America. So my attraction to this stuff is political and personal. MIA and Fela are both explicitly political, while Hardy and Shiina come from countries I've lived in.

One of Wilson's arguments is that because Celine is Quebecoise, people around the world hear her as just slightly non-American. He might have said more about why this is attractive to so many people right now, but the fact that she's huge in Iraq right now is a huge hint. People can hear the positive aspects of America, especially the rags-to-riches dream, without also hearing the music as culturally oppressive. My point is that my appreciation of foreign music (and movies too, probably) is the mirror image of their appreciation of Celine. Both tastes are structured around an understanding of America as the cultural superpower, both attractive and threatening.

Which is also to say that if I were Iraqi, then maybe I'd like her too. But I'm American, so I think she sucks.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Double Feature

During the summer, the Harvard Film Archive creates double features out of entirely unrelated movies that have surprising similarities. My favorite was Mouchette, which ends with a drowning and church bells, followed by Don't Look Now, which starts with church bells and a drowning.

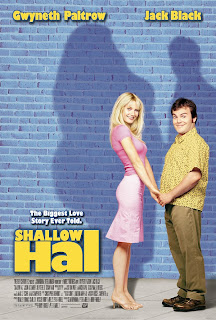

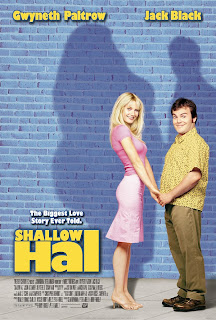

Last night I accidentally saw a double feature of my own: Shallow Hal followed by Washington Square. Both movies feature women whose beauty is, let's say, not immediately obvious. Both women have lovers who see their true beauty, and fathers who don't.

In Shallow Hal Jack Black getsput under a gypsy curse hypnotized by a motivational speaker to see only people's inner beauty, and falls in love with Gwyneth Paltrow, fat but nice. Misunderstandings and hijinks ensue. This might be a better movie than it looks--I saw it on TV so it's hard to judge. Is it actually a parody of make-the-hot-actress-ugly Oscar bait? Could be. If you ignore the giant-underwear gags, a lot of the uncomfortable moments come from the directors playing with film grammar. There are times when you know a cut to Paltrow is coming, but you don't know whether it will be the hottie or the fattie. It's impossible to watch this movie simply to ogle Paltrow. Or to put it in academic speak, our expectations of a fetishizing male gaze are undermined, which is a neat way to provide a distancing effect.

Washington Square was towards the end Jennifer Jason Leigh's 90's hot streak, and the role is perfect for her. The issue here is social skills instead of hyper-obesity, so the mumbling actually works to her advantage. She's hands down the best mumbler in film, and she shows it here.

The direction by Agnieszka Holland is flashier and more "prestige." I'm not sure what the long opening tracking shot was supposed to accomplish, or why she puts so many distractions in the foreground. Even in the shot above there's a sleeve in the way--is that an attempt to disrupt the shot-reverse shot dynamic? No dice, suture is still in effect here, so it looks more like a compromise to make the pan-and-scan process easier. If you're not going to use the whole frame, why shoot in widescreen? I don't mean to pick on this film, since this is pretty common. Sometimes it works, but this is not exactly a Bourne film.

And it shouldn't be. Bourne is intensified continuity, and Shallow Hal uses continuity for gross-out moments; what we want from a female director is another way of looking at the story. We get a little of that, but a whole lot more melodrama.

Still, I liked it. And it was funnier than Shallow Hal.

Last night I accidentally saw a double feature of my own: Shallow Hal followed by Washington Square. Both movies feature women whose beauty is, let's say, not immediately obvious. Both women have lovers who see their true beauty, and fathers who don't.

In Shallow Hal Jack Black gets

Washington Square was towards the end Jennifer Jason Leigh's 90's hot streak, and the role is perfect for her. The issue here is social skills instead of hyper-obesity, so the mumbling actually works to her advantage. She's hands down the best mumbler in film, and she shows it here.

The direction by Agnieszka Holland is flashier and more "prestige." I'm not sure what the long opening tracking shot was supposed to accomplish, or why she puts so many distractions in the foreground. Even in the shot above there's a sleeve in the way--is that an attempt to disrupt the shot-reverse shot dynamic? No dice, suture is still in effect here, so it looks more like a compromise to make the pan-and-scan process easier. If you're not going to use the whole frame, why shoot in widescreen? I don't mean to pick on this film, since this is pretty common. Sometimes it works, but this is not exactly a Bourne film.

And it shouldn't be. Bourne is intensified continuity, and Shallow Hal uses continuity for gross-out moments; what we want from a female director is another way of looking at the story. We get a little of that, but a whole lot more melodrama.

Still, I liked it. And it was funnier than Shallow Hal.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

When Legends Gather

Check out If Charlie Parker was a Gunslinger... Lots of great stuff.

Georges Sadoul, Madame Kawakita, Donald Richie.

Georges Sadoul, Madame Kawakita, Donald Richie.

Monday, February 25, 2008

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Thursday, January 03, 2008

Last Days of Pompeii

The vicissitudes of film preservation (or lack thereof) have turned The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) from a solid tableaux epic into an analysis of film representation. Also possibly a meditation on classicism and modernism in the approaching fascist years. The print is damaged exactly where it should be, in the eruption scene, proving that great art can sometimes occur accidentally.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)